In the quiet moments between class bells and Zoom calls, many of us—parents, educators, school leaders—have felt it.

That gnawing question: Are we doing enough to protect our kids in a world that never powers down?

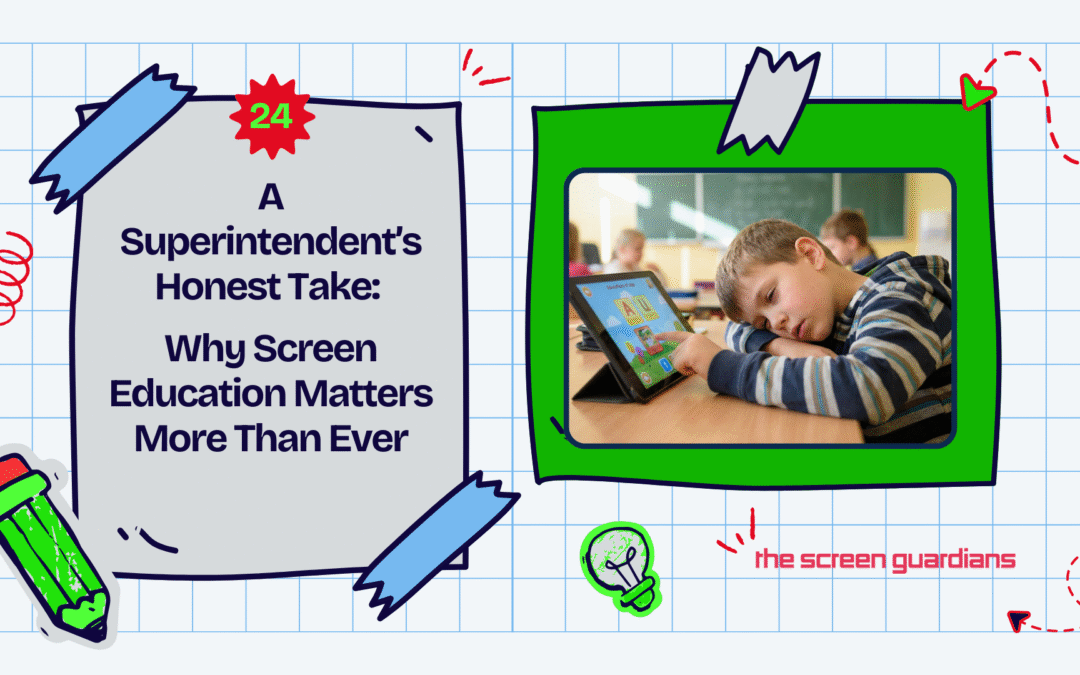

In recent years, digital safety in schools has become more than a technology issue. It’s become a health issue, a learning issue, and—at times—a crisis of connection. Across the country, we’re watching the consequences of unchecked screen time in schools show up in classrooms, lunchrooms, and homes. Children are struggling with focus, sleep, social skills, and emotional regulation. Teachers are seeing attention spans shorten and behaviors change.

And yet, so many of us are still asking: What can we actually do?

Today, we invite you into a conversation with someone who’s not just asking the hard questions—but doing something about them.

Superintendent Paul Larkin of Syracuse USD 494 has spent over three decades in education. He’s watched technology evolve from chalkboards and overheads to Chromebooks and content filters. What he’s seen—and what he’s choosing to do now—offers a grounded, honest look at what’s really happening in our schools and how we can respond with clarity, calm, and care.

Because the goal isn’t to turn back time. The goal is to create a healthier digital path forward—for every student, in every classroom.

Starting now.

Table of Contents

How a rural Kansas district is leading by example.

An in-depth conversation with a veteran superintendent on why digital safety isn’t optional—and how a rural Kansas district is leading by example.

When I first sat down with Paul Larkin, superintendent of Syracuse USD 494 in Western Kansas, I wasn’t expecting a conversation that would stay with me for days.

There was no script. No sweeping rhetoric. Just truth—clear, steady, and hard-won.

Paul has served in public education for more than 30 years—as a teacher, coach, principal, and now as superintendent for nearly a decade. He’s seen technology arrive and evolve in classrooms. He remembers the time before cell phones. He was there when the “one-to-one device” model was first celebrated as a tool for equity.

And now?

Now, he’s watching kids fall asleep in class after scrolling on school-issued devices until 3 a.m.

Now, he’s listening to kindergarten teachers say: “We’re done—we don’t want iPads in our classrooms anymore.”

Now, he worries—not because he’s anti-tech, but because he’s honest about what’s happening.

“It’s almost educational malpractice if we don’t do something,” Paul said. “Five or ten years ago, maybe we didn’t know. But now? If we don’t see it—our heads are in the sand.”

When filters aren’t enough

Most schools have digital filters. Syracuse does too. But when Paul walks the school halls during the last minutes of class, he sees teens lined up at the door—anxiously waiting to grab their phones.

Even with filters in place, students find workarounds. They access content they shouldn’t. They spend hours—sometimes entire nights—on devices that were supposed to support learning.

Paul made the decision to bring in the Screen Guardians program because he realized: restrictions alone weren’t enough.

He wanted education.

He wanted a solution that went deeper—into homes, into habits, into hearts.

“One-day assemblies aren’t going to change anything,” he said. “We have to teach our kids, our staff, and our families how to build something different.”

A rural town with a big heart

Syracuse is a small, agricultural community—65% of the students are English Language Learners; nearly 70% qualify for free and reduced lunch. But make no mistake: the size of the town has no bearing on the size of its dedication to kids.

At a district-wide parent event for The Screen Guardians program, families showed up with questions. They didn’t want platitudes. They wanted clarity:

- “What exactly will my child be learning?”

- “How can I support this at home?”

Those conversations helped shape the final touches of our Parent Companion—a week-by-week resource that welcomes families into the learning experience.

Because this isn’t about telling people what’s wrong.

It’s about walking alongside them as we work toward what’s better.

Finding a way forward, together

When I asked Paul what gives him hope, his answer reminded me why we do this work.

“Kids want to do good,” he said. “And adults in schools—we want what’s best for them. Once we know what to teach, we’re good at teaching it. That’s what we do.”

In Syracuse, that starts with honesty.

A willingness to say: “We’ve let some of this go too far.”

And the courage to say: “We’re not going to look away anymore.”

Change rarely comes in sweeping gestures. It comes in rooms like Paul’s—with a school board, a community team, and a group of kindergarten teachers saying: “Let’s do things differently.”

It starts when someone stands up and means it.

Just like Paul did.